6 minute read

Prelude

It is now a truism to say that technology has become ubiquitous. In 1978, electronic music band Kraftwerk released one of its many classics: “We are the robots“. It came nearly thirty years after Isaac Asimov’s landmark science fiction book of short stories “I, robot” which was an early reflection on the reflective power and moral rights of artificial intelligence. Today, artists like Squarepusher push the logic of machinic intelligence and reasoning to new artistic boundaries in a playful, mesmerising, but also ominous way. Electronic music is one of many ways in which we are welcoming the machine into every aspect of our everyday life.

The machine is not only everywhere, it operates from a place of nearly self-conscious agency. In some ways, it knows more about us than we do about ourselves, and learns to know itself in the process. Science fiction is perhaps the greatest way of exploring machinic metaphysics at length.

We also like to think machines make our work easier – or harder, depending on whether they actually add more work to our list when they don’t function as we would like them to. It takes quite some work to learn to think like machines so we can tell them to think nearly like us. All the credit, and errors, remain ours ultimately. The machine is shaping our way of being in the world, just as much as we are reshaping machines to engineer new versions of ourselves, with all our most noble aspirations and poorly-acknowledged imperfections.

Machines therefore play a crucial part in our lives. But do we know exactly how? This post provides a high-level map of how people and tech cooperate to build the foundations for a digital planning system, with a special focus on software for community engagement.

Welcome to the cyborg

In a former post, I discussed some of the many ways in which we are becoming more like cyborgs. Technology is increasingly becoming a direct extension of our interaction with the world. Every aspect of town planning and construction promises to reinforce the digital, as part of the the push toward ‘digital first’ public service delivery and the development of tech-empowered smart cities. However, there is a clear risk of favouring blunt data-driven decisions at the expense of knowledge-enriched decisions and truly reflective insight. Many of the latest advances in internet technology and software development do show signs of being people-centric rather than system-centric, building on a long tradition of user-centric studies and application development in the field of human computer interaction (HCI). Notwithstanding, current debates about the pervasiveness of AI in society does generate diverse views – see for example evaluations of the EU AI Act, or doing a google search of the wider range of actors involved in leveraging ‘data for good‘. AI and its countless applications has profound implications for town planning and the built environment, from semantic linked data and Digital Twins to Alibaba’s ‘city brains‘ and semi-automated development management / ‘back-office’ planning system (BOPS) for local authorities.

To be sure, machines aim to please and make our work easier, if only asked in the right way.

The web of actors

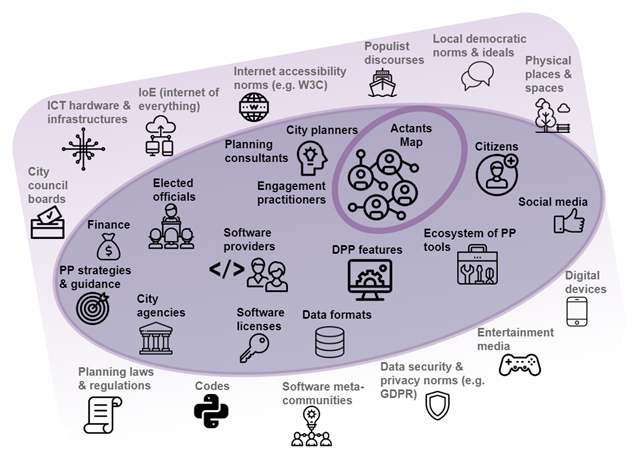

The following map provides a high-level overview of all human and non-human actors that directly shape the market and practice of digital engagement in urban planning. It is an unpublished output from my PhD thesis, created with inspiration from the Actor-Network Theory (ANT) of Bruno Latour, John Law, and others.

In essence, and for the sake of oversimplification, ANT puts people, ideas, concepts, technology, the physical environment and other artefacts on a equal footage as regards their ‘agency’ or impact in the world. The term ‘actant’ extends the notion of ‘actor’ to non-human counterparts. More than an intellectual exploration, ANT is a dispassionate observation that laws, technology, people and ideas about the world recursively shape each other through everyday practices. It is about looking at the way things operate in practice. It is no longer enough to speak of market actors or policy actors. Each and everything contributes to reshape the world in its own image, through its interaction with other parts of the network. Nearly any ‘thing’ or ‘person’ can be empirically observed to shape the world as actant, if agency it does have.

Figure credits: Original elaboration by the author.

The diagram is exploratory. It provides food for further analysis and discussion, as well as a template for adaptation and re-use. The diagram does not aim to be exhaustive or universal. It investigates all the actants involved in the adoption and use of digital particiaptory platforms (aka Civic Tech or community engagement software) in urban planning. At the centre of the diagram are the actants whose role seems most important, as emerging from my empirical PhD findings about the design of digital engagement projects. To name but a few, these are: city planning professionals, engagement professionals, digital participatory platforms (‘DPPs’), citizens, digital software providers, and the ecosystem of tools for public participation that may be used for any specific project or across projects.

On the edges of the map one finds local places and spaces, nationalist political discourses, planning laws and regulations, and the ubiquitous presence of digital devices in society. All of these, and other factors not on the map, shape the way people interact with digital software for public participation (DPPs) more or less directly. Linking the core and the periphery, I have found that local councils can particularly benefit from having a clear engagement strategy from the outset, not just for an individual project, for the city agency as a whole. Being clear about what public participation is at a city level can help remove misunderstandings and unrealistic expectations for citizens as well as city staff and elected officials. Examples of clear engagement strategies include the engagement strategies by the city of Longmont (Colorado) and the city of Grenoble (France), to cite but two among many others.

The actants situated on the edges matter nearly as much, because they may be taken for granted. Their agency is no less real. Loss of trust in political processes, or in the semantic web and the many algorithms that pervade it, many rob citizens of trust in the efficacy of digital participatory platforms in shaping the places they inhabit. It therefore takes a network to understand the parts. Put differently, it is only by engaging with the sum of the parts that we may engage with each part most effectively.

Applications and future work

The value of the diagram lies primarily in becoming acutely aware of all the taken-for-granted pieces of policy, technology and the many actors whose agency in urban planning is sometimes disguised, forgotten, or worse still, silenced. It is also a sobering reminder that people, technology, and institutional processes shape each other recursively. In a practical perspective, to omit the interdependencies between the different actants increases changes of failing to engage communities effectively, which could have devastating effects on local climate action, the quality of urban development, sustainable mobility, and other areas of urban planning. It pays to draw one such map for every project or planning context at the scoping stage. Updating it regularly will also help refine one’s understanding of the complexity of the project at hand without forgetting to engage with all the right actants.

More elaborate empirical investigation and data analysis could investigate the strength of the relationships between the different actants in the network. Any such analysis would remain subjective, however, or loaded with assumptions on the part of the analyst.

Although exploratory, the diagram can provide a decent template to start with, and adapt according to the specificities of the project, the range of key actants and geographical conditions. It can also complement wider efforts to select and evaluate software for community engagement. One can cite for example the Guide to Digital Participation Platforms and the supporting descriptive matrix of DPP software published in January 2022 by People Powered.

With your feedback, the diagram could also be refined or adapted to different contexts across the built environment. The next frontier lies in making digital participatory planning more self-consciously reflective and people-centred, rather than tech-driven per se or focused on cost reductions alone. True cyborgs are capable of fusing the best of machinic reasoning and human wisdom to serve their (hopefully altruistic) needs.