6 min read

Prelude

We already knew the old adage before the pandemic: ‘place matters’. Place mattered all the more when working from home (#WFH) became a new habit for countless knowledge workers. One way to make places more attractive and healthy is to promote walkable, mixed-use neighbourhoods characterised by quality, accessible green space and a range of other amenities. This is the crux of multiple strands of work in global urban design practice and theory, including ‘tactical urbanism‘, ‘urban acupuncture‘, ‘placemaking’, ‘new urbanism’, and city-making that fosters the ‘creative class‘.

But how do we do it – exactly?

With good urban design, of course. But also with data. Since place matters, data about places matters just as much. The right kind of quality data can augment our common sense and our expert knowledge of places to provide new insight about places and the people they inhabit. Data can both elucidate and interrogate the burning questions of our day about sustainable placemaking, which can then elicit further questions to investigate.

This post provides a synthesis of the excellent webinar hosted by the Town and Country Planning Association on 21 June 2022, the third installment in a series about 20-minute neighbourhoods. The webinar featured engaging and informative presentations by Gemmy Hyde, project and policy officer for Healthier Places at TCPA, Andy Lindop, principal planning officer at Birmingham City Council, John Herbert, Director at Troy Planning and Design, and Andrew Netherton, Healthy Places programme manager for the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities.

Keep posted on TCPA’s YouTube channel for the recording when made available, and to watch past webinars. In the meantime, below are a few takeaways.

Disclaimer: this is a selective summary, based on my biased appreciation of the topic, rather than a verbatim transcription of the webinar.

20-minute neighourhoods

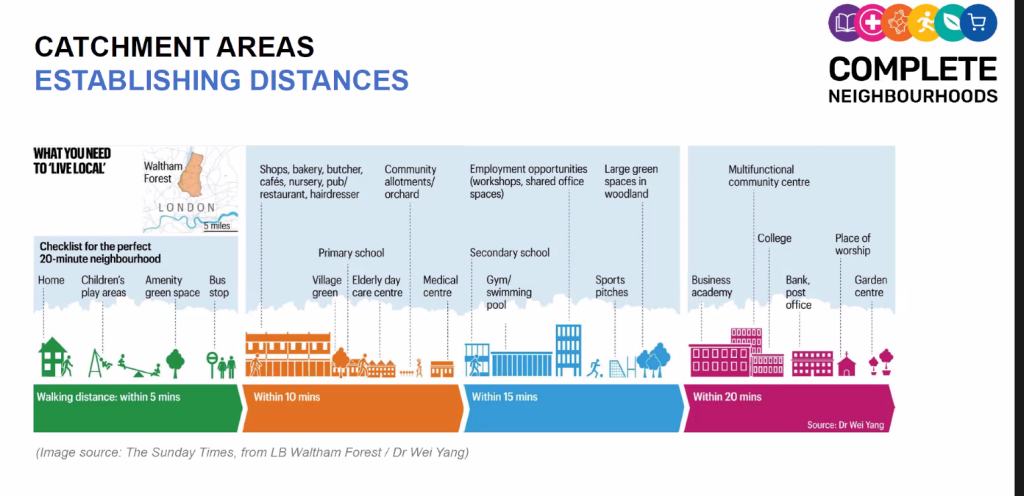

Gemma Hyde, project and policy officer for Healthier Places at TCPA, presented a brief state-of-the-art about the rationale and practical considerations for well-functioning neighbourhoods. The ’20 minute neighbourhood’ is an urban design and planning concept built around the idea that a wide range of essential day-to-day services could be accessible within a 20-minute walk (on average). This includes key local amenities such as quality green space, shops, local schools, a diversity of affordable homes, local food production, a healthy built environment, access to public transport and other services. In a nutshell, this calls for places that are complete, compact and connected. If there are three words to remember from the webinar, it is these. There lies the crux of the 20 minute neighbourhood; a simple mnemonic to guide neighbourhood retrofits and new developments alike.

Completeness refers to the interconnected combination of the aforementioned local services. It is a guide, not a rule. Compact neighbourhoods provide everything you need where you live and work, which may be linked with urban intensification, regeneration efforts, and transit-oriented development (TOD). Connectedness implies good public transport, intermodal travel hubs, walkability, and cycling infrastructure. Neighbourhoods should be age- and ability-friendly to be truly inclusive and accessible to all, which also includes children, who will naturally ‘inherit the Earth’.

What about data? Collecting the right data can help establish the baseline to evaluate current opportunities and challenges, based on evidence rather than hunches. Data can also empower change, which we know is difficult by nature. Data can also support well-informed communication, dialogue and add collective insight to personal knowledge. Data is not a panacea, due to variations in availability, quality, consistency, extent, and assumptions about how it was produced, but remains essential to better understanding places. Risks include the clouded judgment that arises from relying on noisy data, data of poor quality, or unsatisfactory proxy data. Data can therefore hinder insight rather than enhance it. Trustworthy data analysis and interpretation should aim to go beyond boundaries, such as artificial or overlapping geographical boundaries, or siloed understandings of the interdependent features of well-functioning places. Data-augmented knowledge should therefore endorse transparency and a strong commitment to provide a synergy in local services.

Healthy Living Zones in Birmingham

Andy Lindop presented work at Birmingam City Council around the creation and operationalisation of healthy living zones. ‘Healthy Living Zones’ implement a concept somewhat similar to that of the ’15-minute neighbourhood’. The approach connects with the non-statutory ‘Our Future City Plan‘ strategic document, the City of Nature Plan for green infrastructure and its related consultation documents, the Transport Plan that aims to reduce journey times, and the East Birmingham Growth Strategy to tackle deprivation in the area. In essence, the relative proximity of quality local services is a principle more than science or steadfast rule, and “exists on a continuum”. The key is to foster sustainable, low-traffic neighbourhoods rather than exact time distances for each type of service.

The East Birmingham Spatial Pilot has been launched to test an in-house methodology for measuring and designing ‘healthy living zones’ to help tackle deprivation in areas such as Bordesley Green. The approach hinges on GIS measurement indicators as well as active engagement and dialogue with hard-to-reach residents in the area, characterised by a young population. Supporting projects include walking and cycling audits, the work of ecobirmingham’s environmental coalition, and others.

The methodology and concept of a healthy living zone has rested on extensive GIS analysis and a better understanding of residents’ perceptions of their area. A mix of hexagon-based and LSOA-based (i.e. Lower Layer Super Output Area) boundary analyses of the area were performed to help define the pilot area, and linking these with existing cross-sectoral policies. In short, there is no perfect way to go about determining a suitable area and its boundaries for healthy living zones. The pragmatic approach enabled to develop the ‘Healthy Living Zone Toolkit’ for use across the city council and wider dissemination.

Beyond spatial analysis of trends and needs in the area, more data can be collected through surveys about housing and infrastructural needs, air quality measurements, assessments of fair access to parks, monitoring of urban heat islands, pedestrian counts, and rapid health impact assessments derived form the London Healthy Urban Development Unit (HUDU). In conjunction with the above, an EU-funded project with Birmingham City University aims to train and work with community researchers to produce highly relevant, fresh data about experiences of the area from local communities. Political spearheading of such community-wide projects is also key for their long-term effectiveness.

Complete neighbourhoods in southeastern Essex

John Herbert at Troy Planning and Design presented ongoing urban design and planning work in Southend and Rochford to create ‘complete’ neighbourhoods for the ’10-minute town’ (see also how Dunbar in Scotland have been doing it). Baselines were conducted to assess the availability of services and facilities within specific walking catchments, such as health, education, retail and open space. These walking catchment assessments are fundamental to assessing an area’s ‘completeness’. Indeed, in the absence of quality data and collective commitment, there is always a risk of seeing the 20-minute neighbourhood concept deployed in wealthier areas only. Complete places must be inclusive and benefit everyone.

Experience also shows people are willing to travel longer for specific types of quality services. Common examples include accessing secondary schools, theatres, and large open spaces. Therefore, while concepts like the 10-minute town and the 20-minute neighbourhood are powerful urban design frameworks, the same walking catchments cannot apply to every type of service.

A wide range of data and evaluation methods can be utilised and compared. Spatial analysis in the form of heat-map analysis of different service catchments can be overlayed and compared. Spider diagrams and other simple visualisation methods can help assess and communicate how neigbhourhoods perform in terms of completeness. Different metrics also need to be reconciled and implemented with a critical eye when designing urban interventions. Factors such as population density must be considered, where areas that are already dense might not provide opportunities for further urban intensification. Furthermore, research also shows there are no direct correlations between an area’s degree of completeness and indices of multiple deprivation (IMD). A thorough evaluation of the distribution of transport infrastructure and services of day-to-day importance can help inform development interventions such as transit-oriented development (TOD). Context therefore matters. In the case at hand, towns such as Southend and Rochford share similar characteristics but also have remarkably different population densities. Approaches to improve neighbourhood completeness should therefore be bespoke as well as evidence-based.

The research behind such local analyses and interventions is truly global. Among other cities, it builds on cutting-edge research conducted in Portland, Melbourne and Paris. It is also informed by an appreciation of ancient forms of placemaking, such as agoras. It also largely builds on the work of urban designers such as Hugh Barton (such as the reference book Shaping Neighbourhoods), and the work of the Place Alliance led by Matthew Carmona and co-founded by Lucy Natarajan.

On a critical note from my own perspective, implementation of the ‘complete neighbourhoods’ concept must be reflexive. It is fair to say Paris is not quite like Southend-on-Sea: while new cycling infrastructure and placemaking interventions in Paris have been lauded internationally, it also leads to increased congestion and public frustration in the French capital. There is a real war between cyclists and car-drivers the world over, which is at least partly the product of decades of modernist transformations of cityscapes. Which begs the following related questions: for whom do we roll out 20-minute neighbourhoods? And where do the neighbourhoods begin and end? To paraphrase Jean Lefebvre: do long-distance commuters also have the ‘right to’ the 20-minute neighbourhood?

Systematic review of 62 frameworks for healthy neighbourhoods

Andrew Netherton, Healthy Places programme manager at the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, presented a recent evaluation a wide range of existing frameworks that seek operationalise and assess healthy neighbourhoods in the built environment. The presentation reviewed tools such as the Scottish PlaceStandard tool. The research builds on the premise that public health is shaped by interlocking factors, such as social determinants as well as the overall quality of the built environment. The main findings of the systematic review are that frameworks tend to either focus on specific types of places or dimensions of public health. Few frameworks, therefore, provide a holistic, comprehensive approach to the design and evaluation of healthy neighbourhoods. The research identifies the following key components for an effective, evidence-based framework:

- A consistent and comprehensive approach to “what good looks like” for healthy neighbourhoods

- Coordinates local systems and data to identify areas of improvement

- Enables collaboration at all spatial scales and levels of agency (community, local authority…)

- Easy to use for local communities

- Evidence-based and actions-oriented

- Enables to monitor change, evaluate and provide continuous improvements

- Empowers cross-cutting place-based approaches and planning

Critically, the research also highlights the lack of a national public health-centered reference point for building healthy places in England.

Next steps include a commitment to develop and trial a robust holistic framework through pilot projects steered by appropriate governance and advisory groups. Doing so will also help support the Levelling Up agenda by DLUHC and the Health Disparities White Paper. This also includes promoting the use of the PlaceStandard tool across England, which has already been tried-and-tested compellingly across Scotland. This and build capacity and capability accordingly.

Going forward, this essential piece of research can also be seen to support the upcoming publication of statistics for the Public Health Outcomes Framework in November 2022 that will help local communities better understand trends in public health in specific places.

Data matters for complete neighbourhoods – it’s work in progress!

While a solid foundation is already being built in terms of data and holistic approaches to healthy, complete neighbourhoods, it’s still very much work in progress. A positive insight is that people of all walks of life tend to relate with the idea of a ’10 minute town’ or ’20-minute neighbourhood’. Although complex to apply in practice, the principle of complete neighbourhoods is relatable, as opposed to much jargon found among professionals in town planning, urban design and public health.

Further reading

Based on the rich insight shared in the webinar, one must also cite the following resources:

Implementing 20-minutes in Scottish planning through such means as place-based parternships, development management, and local place plans – a report by RTPI Scotland (2021).

Shaping Neighborhoods, an urban design book by Hugh Barton (2021).

The Design Skills in Local Authorities in England report, which identifies gaps in design skills at local authorities, by the Place Alliance. The report warns that “the absence of design expertise locally will result in a new generation of substandard developments”.

The Cornwall Design Guide, an exemplar of how design codes can help create complete places and integrate the orientations of climate action plans into the built environment, by Cornwall County Council (2021).

The Data Trusts Initiative, a cross-sectoral data partnership which helps connect people, places and public health through digital data, based on insight from recent research and ongoing pilot projects.